7/20/05

The Allegory of the Cave

Plato (375 B. C. E.)

This piece details Plato’s allegory of the cave presented in his work Republic. (514a-520a, Book VII)

Translated by Shawn Eyer.

Parts of the passage have been redacted to exemplify the point of the text.

SOCRATES: And now allow me to draw a comparison in order to understand the effect of learning (or the lack thereof) upon our nature. Imagine that there are people living in a cave deep underground. The cavern has a mouth that opens to the light above, and a passage exists from this all the way down to the people. They have lived here from infancy, with their legs and necks bound in chains. They cannot move. All they can do is stare directly forward, as the chains stop them from turning their heads around. Imagine that far above and behind them blazes a great fire. Between this fire and the captives, a low partition is erected along a path, something like puppeteers use to conceal themselves during their shows.

GLAUKON: I can picture it.

SOCRATES: Look and you will see other people carrying objects back and forth along the partition, things of every kind: images of people and animals, carved in stone and wood and other materials. Some of these other people speak, while others remain silent.

GLAUKON: A bizarre situation for some unusual captives.

SOCRATES: So we are! Now, tell me if you suppose it’s possible that these captives ever saw anything of themselves or one another, other than the shadows flitting across the cavern wall before them?

GLAUKON: Certainly not, for they are restrained, all their lives, with their heads facing forwards only.

SOCRATES: And that would be just as true for the objects moving to and fro behind them?

GLAUKON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Now, if they could speak, would you say that these captives would imagine that the names they gave to the things they were able to see applied to real things?

GLAUKON: It would have to be so.

SOCRATES: And if a sound reverberated through their cavern from one of those others passing behind the partition, do you suppose that the captives would think anything but the passing shadow was what really made the sound?

GLAUKON: No, by Zeus.

SOCRATES: Then, undoubtedly, such captives would consider the truth to be nothing but shadows of the carved objects.

GLAUKON: Most certainly.

SOCRATES: Look again, and think about what would happen if they were released from these chains and their misconceptions. Imagine one of them is set free from his shackles and immediately made to stand up and bend his neck around, to take steps, to gaze up towards the fire. and all of this was painful, and the glare from the light made him unable to see the objects that cast the shadows he once beheld. What do you think his reaction would be if someone informed him that everything he had formerly known was illusion and delusion, but that he was a few steps closer to reality, oriented now towards things that were more authentic, and able to see more truly. And, even further, if one would direct his attention to the artificial figures passing to and fro and ask him what their names are, would this man not be at a loss to do so? Would he, rather, believe that the shadows he formerly knew were more real than the objects now being shown to him?

GLAUKON: youve got me all wrong.

SOCRATES: Now, if he was forced to look directly at the firelight, wouldn’t his eyes be pained? Wouldn’t he turn away and run back to those things which he normally perceived and understand them as more defined and clearer than the things now being brought to his attention?

stop talking to me.

Ophelia

John Everett Milliais (1851-1852)

This piece depicts Ophelia from Shakespeare’s Hamlet singing before she drowns in a river, modeled after the scene Gertrude describes in Act 4, Scene 7.

Gertrude

There, on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds

Clamb’ring to hang, an envious silver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide

And mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up;

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and endued unto

that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

what makes you think that?

what makes you think that thats me, asshole?

youve got me all wrong. you dont know me.

so get me out of here already. this isnt where i should be.

hello?

Christina’s World

Andrew Wyeth (1948)

The painting depicts Anna Christina Olson (5/3/1893-1/27/1968) who had a degenerative muscle disorder. This left her unable to walk, but she would refuse to use a wheelchair. She opted to crawl everywhere. Wyeth saw her crawling across a field while he was watching from a window.

i dont feel right.

it feels like someones trying to fuck with my brain. showing me all these things like im a fucking lab rat.

do i deserve this?

i know ive done bad things but when is enough enough?

because, if you ask me, fucking with peoples brains is enough.

leave me alone

i know youre watching you sick fuck.

come help me i cant move. i cant breathe/0;—————

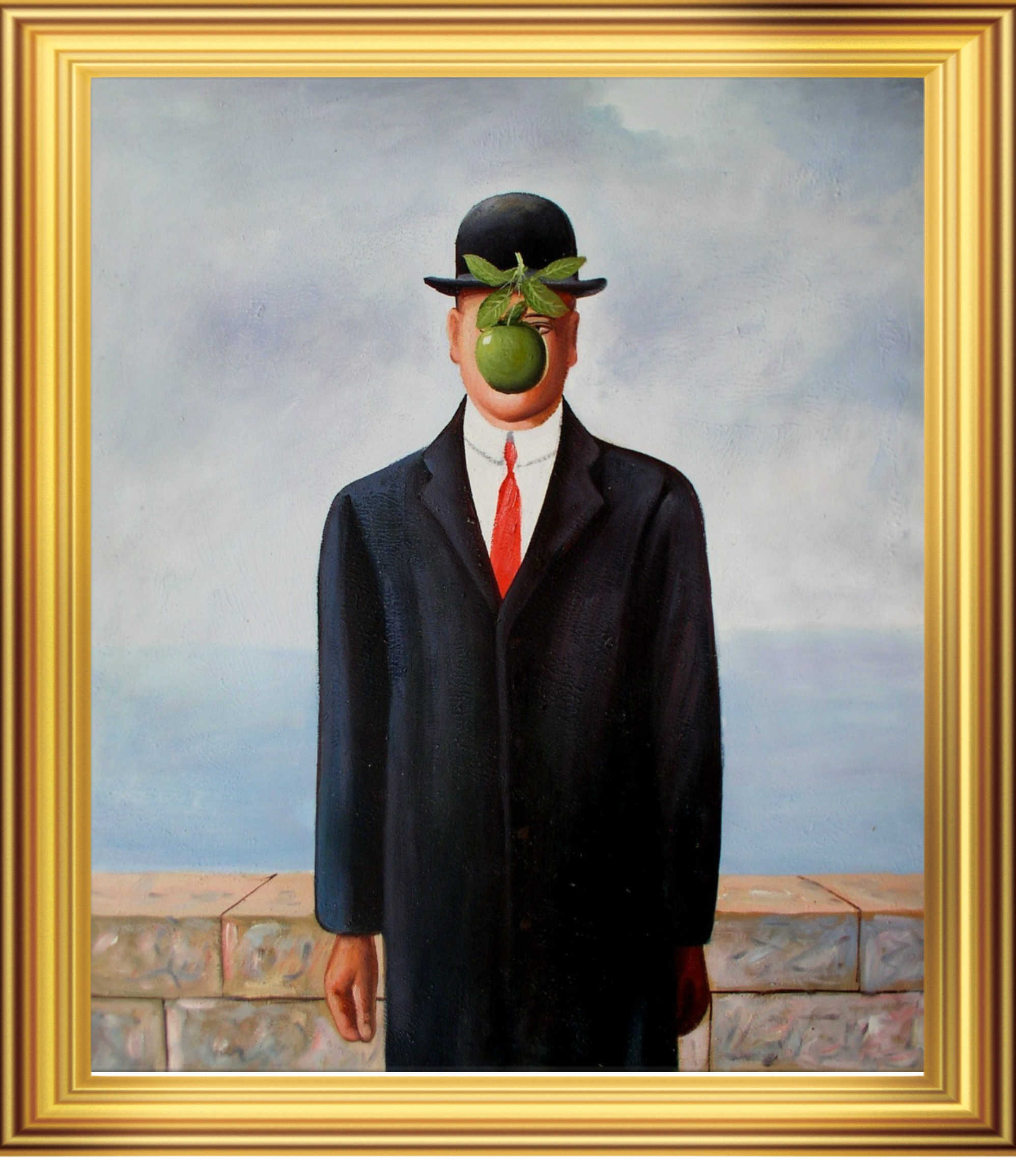

The Son of Man (French: Le fils de l’homme)

Rene Magritte (1964)

This painting is a self-portrait.

Magritte on the painting:

"At least it hides the face partly well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It's something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present."

dumbass painting. whoever drew this should feel bad. you fucked his arm up.